|

I am drawn to Mark’s Gospel in good part because of its simplicity. It is the least adorned of the four canonical Gospels. It does not shy away from presenting Jesus in His real human nature. It does not introduce Jesus to the reader through angelic chorus or epiphanies associated with His birth. It does not reach back through time immemorial to pronounce Him abiding with God before creation. Mark, instead, introduces us to the abrupt news that Jesus is the “Son of God” (1:1) when and in similar fashion Jesus is introduced to the startling revelation of “‘You are my Son.’” (1:11) This is not a tranquil, gradual realization for reader or for Jesus. Mark portrays the baptism as Jesus, and only Jesus, seeing the heavens “torn apart.” The Greek word is σχίζω (sxizo). It is the same verb used at the end of the Gospel to describe the violent tearing of the Temple curtain upon the death of Jesus. It is the root of the English word schism, which is the tearing away of one part of the church from another. It is a forceful even terrifying revelation in the sense that Jesus is confronted with a reality that is imposing and daunting. There must have been persuasions before this dramatic moment, but they seem to have left Jesus wondering about who He is and what He is supposed to do. This is why Jesus travels from Nazareth to John the Baptist out in the Judean desert. Jesus is searching. Then, when God answers, it is as if the heavens were torn apart. This is not the clouds parting gently and a warm ray of sunshine alighting on Jesus’ face. This is a revelation that “drove” Jesus farther into the desert to face the temptation of what this all meant. The trial is depicted in the mythical terms of Satan, wild beasts and angels, but the heart of the matter is that Jesus struggled mightily with the meaning and purpose of His life ahead. This struggle is repeated for the reader. Mark is the oldest written story of the life of Jesus. Behind the Gospel, there is an early Christian community that must have wondered about its own story and its own place. How is it that they had come to believe when so many others would not? The whole of the Gospel seems to whisper the amazement that the life and teaching of “the carpenter” (6:3) from Nazareth has survived, that even these 40 years later a community of faith has gathered and has persevered, and now desires to pass along to future generations its story of Christ. Mark realizes that this mystery of faith must be repeated person after person, generation following generation. The choice to believe must be based on a personal encounter with the risen Christ, not unlike the experience of Proust’s Madeline cookie. This is why Mark’s Gospel closes so abruptly. There is not a single vision of the risen Lord. Rather, three women encounter “a young man, dressed in a white robe” (16:5) who informs them that Jesus “has been raised.” This so terrifies the women that “they went out and fled from the tomb, for terror and amazement had seized them; and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.” (16:8) And the Gospel closes. To witness the risen Saviour is not for others to speak to the fact, but for the reader to struggle with the faith and hopefully experience the risen Christ directly. I appreciate this connection of struggle. It brings Jesus closer to me. I believe in His divinity, but I cherish His humanity. Jesus is an approachable, empathetic God. He does not only atone as if His most meaningful connection is with me as a sinner. Jesus stands at-one with me as a person in good times and bad, in the sacred and the mundane. He does not sit in heaven. Jesus stands with me where I need Him most. Jesus brings God close, even if that closeness sometimes strikes like an awareness of “the heavens torn apart.” I would rather be startled by Jesus than bored by God. This unaccustomed Saviour is presented to the reader in the beautiful subtlety of a first and last miracle. I remember attending a reading at the Whatley Congregational Church. Mark’s Gospel was memorized by the presenter from start to finish. He shared the Gospel as a story-teller would in one sitting. It added a new vibrancy to the text. Often, we read the Gospel, if we read the Bible at all, in segments that are separated by a day or days. In such a situation, the connections intended by the author may be lost. I believe there is a long-distance connection between one of Jesus’ first miracles and His last. Still in the first chapter, Mark tells of Jesus’ cleansing of a leper. The stricken man kneels before Jesus begging. He pleads, “If you choose …” (1:40) Is this only a pious humility or is there more to these desperate words? We need to remember that a leper was judged ritually unclean. The disease was an affront to God and the godly. It was not only a physical ailment; it was a spiritual one. The leper was daring to ask the miracle-worker, the acknowledged man of God, to intervene and “make me clean.” (1:40) He must have feared that Jesus’ reaction could be harsh, that how dare a sinner such as he approach and ask for a miracle from God when he was kept a distance by the law of God. The traditional translation of Jesus’ response begins with the phrase: “Moved with pity (σπλαγχνισθείς).” (1:41) There is an alternate translation, however, that often appears as a footnote and it reads: “Moved with anger (όργισθείς).” Pity at first glance makes more sense and seems more in line with our expectations of Jesus, but I think there is merit and meaning to the alternative of anger. Jesus grew angry not at the man, the one suffering before Him with leprosy, the one who feared to approach Jesus and break the religious taboo of separation. Jesus was angered by a religious system that would teach and compel a child of God to be frightened of God in his or her most desperate moments. Jesus rejects this religious callousness of separation by dramatically touching the man, and in that touch God reaches out to him, as well. Jesus takes on Himself the ritual uncleanness of the leper. Jesus becomes at-one with him. I hear sincere compassion for the man and also a deep-felt sorrow because of the system when Jesus answers, “‘I do choose.’” (1:41) There is much confusion surrounding Jesus that Mark does not shy away from in the body of the Gospel. As Jesus marches toward Jerusalem and the fate that awaits Him, three times He prophesies that He will suffer and die, and three times His closest followers fail to grasp what is said. Then, on the last leg of the journey, moving past the city of Jericho, probably wondering if anyone understood Him or His message, pondering the possibility that He may die in vain, Jesus hears a commotion beginning.

Blind Bartimaeus was sitting by the roadside begging for alms. As the pilgrims move past on their way to Jerusalem for Passover, Bartimaeus hears that Jesus of Nazareth is among them. Stories must have preceded the man. Bartimaeus begins to shout out toward Jesus. The crowd orders him silent. They are expecting Jesus to play their role of the Messiah, the conquering, mighty hero who will defeat the Romans and re-establish the glorious kingdom of David. Passover was a celebration of Yahweh’s remarkable intervention against a powerful foe. This expectation fueled the enthusiasm of the crowd marching beside Jesus toward Jerusalem. The confusion intensifies. They have no time for a blind beggar. Jesus has more important matters to undertake. Bartimaeus only yells out the louder: “‘Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!’” (10:47) This is the commotion that Jesus hears, and He calls Bartimaeus over. Opposite the reluctant leper, blind Bartimaeus throws off his cloak, jumps up in excitement and rushes to Jesus. Jesus asks what he wants. There is no “If you choose.” Bartimaeus is clear in his answer: “‘Let me see again.’” All those of clear vision were blinded to Jesus. After an almost complete ministry, they still saw Jesus as they wanted to see the Saviour, not as Jesus had revealed Himself. They were spiritually blind. On the other hand, blind Bartimaeus could see long before the miracle. When others were looking for a Messiah to wield a sword of religious vengeance and who would relish the death and destruction wrought by an angry God, blind Bartimaeus saw a Messiah who would stop on His pilgrimage for a lone beggar beside the road. His Passover Messiah emphasized the divine care and concern for the hopeless. Bartimaeus was healed and followed Jesus on the way joyously. This is a verse full of discipleship terminology. Bartimaeus appreciated Jesus as a compassionate Saviour. And in this, Bartimaeus brought some degree of consolation to Jesus. The Gospel story of this early and last miracle conveys the spiritual progress that a person seeking to follow Jesus must traverse. We must move beyond the image of a fearful God and embrace and be embraced by a compassionate Saviour, by Jesus standing at-one with us. This can also be a “heavens torn apart” revelation. It may shock us with the challenge that Jesus stands at-one with us so that we may work at-one with Him in the sacred task of caring for each other and being stewards of creation. It is to move from being redeemed by Christ to then being re-born in Christ. The awareness of what we can be and what we can do as Christians may be as shocking and unexpected as was Jesus’ “‘You are my Son’” moment. And again, this is why the Gospel has no real ending … because we are still writing it every new day as we carry the compassion of Christ out into the world for people to experience.

0 Comments

Mark 8:22-38 Part TwoIt took only a moment for the traditional expectations of the Messiah to overpower everything that Jesus had hoped to teach and exemplify. Immediately after Peter’s profession of “‘You are the Messiah,’” as noted in Part One, Jesus switches to “Son of Man” language, but even this more pedestrian terminology cannot undo the bravado expectations of these men following Jesus. When Jesus offers His first execution prophecy, they are not only confused. They are offended. The Messiah will be recognized by the accompanying mighty works of God, not by the defeat of execution. Peter even dares to pull Jesus aside and “rebuke” Him. Peter’s profession of Jesus’ Messiahship seems to have been offered as the judgment of all the disciples (Jesus ordered “them” not to say anything), but Peter’s rebuke of Jesus is his alone: “But turning and looking at his disciples, [Jesus] rebuked Peter …” I pause in repeating the remainder of this biblical quotation to emphasize what was obviously intended to be emphasized. Nowhere else in the Gospels does Jesus so forcefully reprimand another person. When Peter confuses the traditional expectation of the Messiah with Jesus’ revelation of the Messiah, the Christ, and when Peter then tries to impose this upon the Messiah, the Christ, Jesus’ words are never harsher: “‘Get behind me Satan! For you are setting your mind not on divine things but on human things.’” Remember the miracle of Jesus’ two-part cure of the blind man? At first, he could only see partially. This must symbolize the spiritual vision of those like Peter who could only see according to their own expectations (“human things”), which blinded them to God’s revelation (“divine things”). Peter, thinking more of his expectations than of Jesus’ example and teaching, is equated with: “‘I can see people, but they look like trees walking.’” A crucified Saviour, a crucified God in the famous coin of phrase of Jurgen Moltmann, is Christianity’s eye exam. When we can see the sacred importance of our crucified God, then this is equated with the fulfillment of the miracle and “his sight was restored.” But Jesus is not yet done. The Messiahship discussion was between Jesus and His disciples alone. Jesus knew the dangers of this topic and it was limited to His closest followers. With the discussion broached and then quickly put back away for another time (And at another time, we can discuss that Jesus next admits to His Messiahship during His hearing before the Sanhedrin when He is asked directly if He is the Messiah, and He answers unequivocally, “‘I am.’”), Jesus then calls together “the crowd with his disciples.” What Jesus is about to say is meant for everyone who would choose to be among His followers. The revelation of Jesus’ execution startled the disciples. For as radical as it was, Jesus takes it further and we can only imagine what it must have been like when Jesus then drops the next bombshell. Not only does Jesus reveal a crucified God, He warns: “‘If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me.’” Only if the disciples and the people in the crowd are willing to accept this revelation of self-sacrifice as faithfulness and virtue, can they then equate themselves with the blind man when “he saw everything clearly.”

Mark’s inspiration is to let each generation of believers face this test of faith. Can we accept a suffering servant of a Messiah rather than a conquering hero of a Messiah? Can we go to the cross with Jesus and see it as His final testimony of true Messiahship? And can we then live our faith accordingly? There are no resurrection appearances in Mark’s Gospel. The question is, therefore, timeless. So, I guess the question is, do we “see people, but they look like trees walking” or do we see “everything clearly.” These are the questions that Bible study encourages. Too often the Bible is cut up and dissected into such little fragments that it can say just about anything we want it to say. The Bible needs to read in a fuller context than this. We need to read, study and pray over the passages as part of a larger whole. This is why I always invite you to come and join us for Bible study. Our next meeting can be found by going to our current monthly newsletter and checking the calendar of events. MARK 8:22-38 PART ONEIn Mark 7, Jesus cures a deaf man by placing His fingers in the man’s ears and His spittle on the man’s tongue. Not the prettiest picture to imagine. Maybe this is the reason why the later Evangelists choose not to retell the story, but Mark has no such aversion. As a matter of fact, at 8:22 Mark begins to tell another such story. This time the man is blind. Again, Jesus touches the man and this time Jesus puts His saliva on the man’s eyes. This time, however, something unexpected occurs. The miracle is not immediately effective. The blind man recovers his sight, but only partially: “‘I can see people, but they look like trees walking.’” Well, this never happens with Jesus-miracles. Jesus tries again. He lays His hands upon the man. This time the miracle is complete; the man sees “everything clearly.” The strangeness of this miracle story should suggest to us that something else is taking place in tandem with the miracle. The only somewhat successful miracle should grab our attention and ask us to think a bit more about the purpose of this story. Many scholars see this as the fulcrum of the Gospel. The balance of the story is about to shift. And does it ever. The Caesarea Philippi declaration at 8:29 was an historically and theologically significant event in the life and ministry of Jesus of Nazareth, and of His followers. It changes the direction of Mark’s Gospel. The symbolism is intentional that Jesus and the disciples are “on the way” when Jesus asks, “‘Who do people say that I am?’” This question and answer are a work in progress. This developmental quality is reflected in the disciples’ various answers. Then I hear Jesus ask in a sullen and uncertain voice, “‘But who do you say that I am?’” He has come to realize that His ministry will culminate in a violent reaction to His person. Jesus searches His closest followers hoping that they at least have an awareness of who He is. Peter answers with words of great insight: “‘You are the Messiah [, the Christ].’” This may be Peter acting as spokesman for the group since Jesus answers quickly with a command to all of them: “He sternly ordered them …”

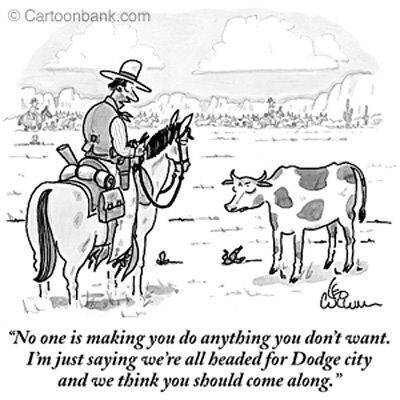

Now that the Messiahship has been broached, Jesus quickly retreats to “Son of Man” language. Messiah was a heavy-laden word in Jesus’ day and one that Jesus did not wish His followers to become distracted by, but Jesus still needed to hear it said. With this bit of reassurance rendered, Jesus chooses immediately to refer to Himself as Son of Man, a self-identification as one among the rest of us. But the effects of Messiah are not that easily forgotten. <To be continued> I’m always inviting people to come and join our Bible study group, but not too many accept the invitation. I ask them to come to at least one Bible class and see what it’s all about, and then they can decide to come back or if it’s not for them. Again, not very many takers. So I thought I would share a bit of a recent Bible study meeting here in this blog. If what follows is at all intriguing, if it at all piques your interest, if it gets you to asking questions, then maybe, just maybe, Bible study is for you, and maybe, just maybe, you may want to consider the possibility of coming to our next class. So let’s begin. At present, we are reading from Mark’s Gospel. It is the first Gospel, as in the oldest, but it is the second book in the New Testament. It’s pretty clear as to why scholars argue that Mark is the first Gospel, but I don’t want to get bogged down in that discussion here. And even though it is the first Gospel, Paul’s Epistles (Letters) to some of his earliest Christian communities date back a full generation earlier. I mention this because I use the “historical critical” method of biblical interpretation. The Word, as in the Word of God, is timeless, but the words used to convey that revelation are most definitely bound within a certain time period, and that time period carries with it the insight and the baggage of that author, that community and that “Sitz im Leben,” which is a technical term in German for “setting in life.” The Bible’s books, in other words, were not written in a heavenly bubble by authors in a spiritual trance. They were written by thinking and inspired authors of faith from a perspective of a particular “setting in life.” Now we are going to move from the general to the specific, and this may be a bit confusing because we lose much of the context that surrounded this particular Bible class discussion, but let’s try and plod ahead anyway. Mark uses the account of Jesus calming the storm on the sea to pose an important question for everyone who encounters Jesus: “‘Who then is this …?’” The nature miracle is important, but Mark is using it to open up a larger discussion. As it is said, sometimes we can’t see the forest for the trees. Jesus goes on to heal a foreigner, then the daughter of a synagogue leader and then again a desperate woman. This is followed by the miraculous feeding of the 5,000, and then there is another nature miracle as Jesus walks on the water. If all of this were not enough, Mark adds a summary statement that people gathered wherever Jesus went and they brought their sick to him to be healed, and all were. If we were reading this story for the first time, if we did not know the end of the Jesus story (which I’m assuming we do), we could assume that Jesus’ ministry was meeting with universal acceptance and enthusiasm and that things would end well. Whichever side of the Sea of Galilee Jesus stood upon, Jewish or Gentile, the power and presence of God were made manifest. Everyone was impressed by this Jesus from Capernaum. This carpenter. But this all begins to change at Mark 7:1. Religious officials from Jerusalem come to investigate for themselves. Prophets and Messiahs are dangerous when they don’t have the decency to first check in with the religious authorities, the establishment, and run their plans by them. Word of Jesus as a wonder-worker has seeped out of Galilee and reached the capital. The high religious leaders travel north to see for themselves what all of this commotion is about up in the hinterlands that this carpenter has instigated. A confrontation is in the making. A skirmish will be engaged to probe for weaknesses. And in this encounter something religiously radical is revealed by Jesus that will again clarify who He is and what should be at the heart of faith and religion. The Jerusalem Pharisees and scribes protest to Jesus that His followers are not maintaining the customs concerning washings. The Jerusalem authorities have traveled long and far to point out that Jesus’ disciples are not washing their hands before eating. Now this may not be hygienic, but when the authorities’ first probe is about such practices as “the washing of cups, pots and bronze kettles,” it reveals a primary orientation toward the practice of religion that is dominated by what is done rather than why it is done. These rules are Pharasaic embellishments of the Mosaic laws. In Exodus, the Jewish priests are ordered to wash ritually before coming “near the altar to minister.” (30:20). They are specifically for priests entering the sanctuary. The Pharisees, with right intention I do not doubt, demanded that all the people keep this law all of the time. Their definition of holiness was ritualistic. Their belief was that the holiness of God demanded the cleanliness of God’s people whom He encountered. The intent was pure: God permeated the entire community not only the Temple; therefore, the laws of the priests became the rules of the populace. But Jesus looked upon the preparedness to be in the presence of God in a radically different manner. Jesus calls out the Pharisees for their embellishment: “‘You abandon the commandment of God and hold to human tradition.’” These Pharasaic practices focused piety on protecting the sanctity of God as if God needed to be protected from imperfect hygiene. God is not Seinfeld’s Bubble Boy. Jesus is going to reverse and turn inside out this religious orientation. Jesus is going to call into question an entire establishment of the religion. The increasing popularity and renown of Jesus among the people who have witnessed His acts of merciful power are now going to be in conflict with the religious establishment. As this occurs, the crowds and even Jesus’ disciples grow confused: “‘Then do you [the disciples] also fail to understand?’”

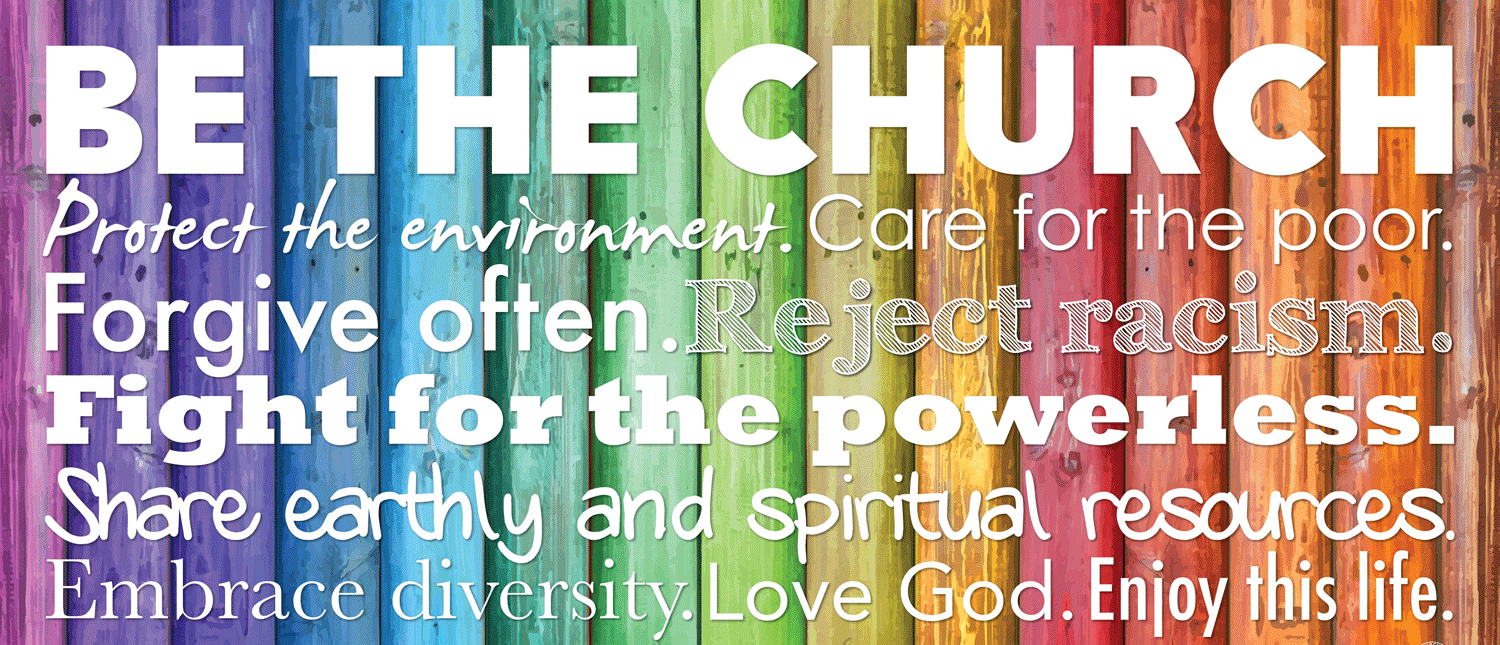

Jesus explains His interpretation of piety. It does not look away from God, but it does see God from quite a different perspective as that of the establishment. Piety, says Jesus, is not defined by an increased stress on rules such as washings. Rather, piety is the distance we place between ourselves and “‘fornication, theft, murder, adultery, avarice, wickedness, deceit, licentiousness, envy, slander, pride, folly.’” These are the sorts of things that “defile” a person. Now look at that list. There are twelve items. Twelve is a biblical number symbolizing completeness. Obviously, this is not a complete list of every possible sin so its completeness must lie elsewhere. Think about what kinds of sins these are. Think about what kind of sins these are not. Each one of them deals with how we treat others. None of them deal specifically with how we interact with God. In response to the establishment’s demand for forms to be followed so that we would not offend the holiness of God, Jesus points to how we treat each other in that exact same context of piety. He’s not forgetting or ignoring God. Jesus is professing a new orientation in the faith. Jesus sees piety as flowing out from our relationship with God and defining our ethics with others: “‘It is what comes out of a person that defiles.’” Can you see how this would disturb the authorities whose religion, again with right and proper intent, was based on the practice of forms? It wasn’t washing bronze pots per se; it was that these practices kept the people ready to be in God’s presence. Then, Jesus, this carpenter from Capernaum, says these are nothing but human practices, that instead true piety before God is found in how we treat each other. This is a fundamental reorientation of religion that Jesus announces and it sets the stage for the defeat and victory of the cross. Jesus reveals that God sees His worship not only in what we do for Him directly, but what we do toward each other. Can you imagine the possible discussions we could hold in Bible study that emerge from this passage? Does church begin with the Prelude and end with the Postlude? Not for the Jesus here revealed. Should church speak out about social justice matters? If we were talking in Bible study about Mark 7, what does the text imply? Is church unnecessary? Not if it’s a form only, but what if it’s an oasis spent with Christ and community for the good of both, and as an inspiration to be Jesus’ hands, feet and voice throughout the world? These are the themes of Bible study that go well beyond retelling the stories. If you’ve made it this far in the blog, I hope you’ll go a bit further and join us for Bible study. Rev. Randy |

NewsFaith, love and chitchat. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

Follow

|

|

SERVICE TIMES

Sunday 9:30-10:30am Children Sunday School 9:30-10:30am Nursery care available during worship DONATE Make a single or recurring contribution by clicking here |

FOLLOW

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed