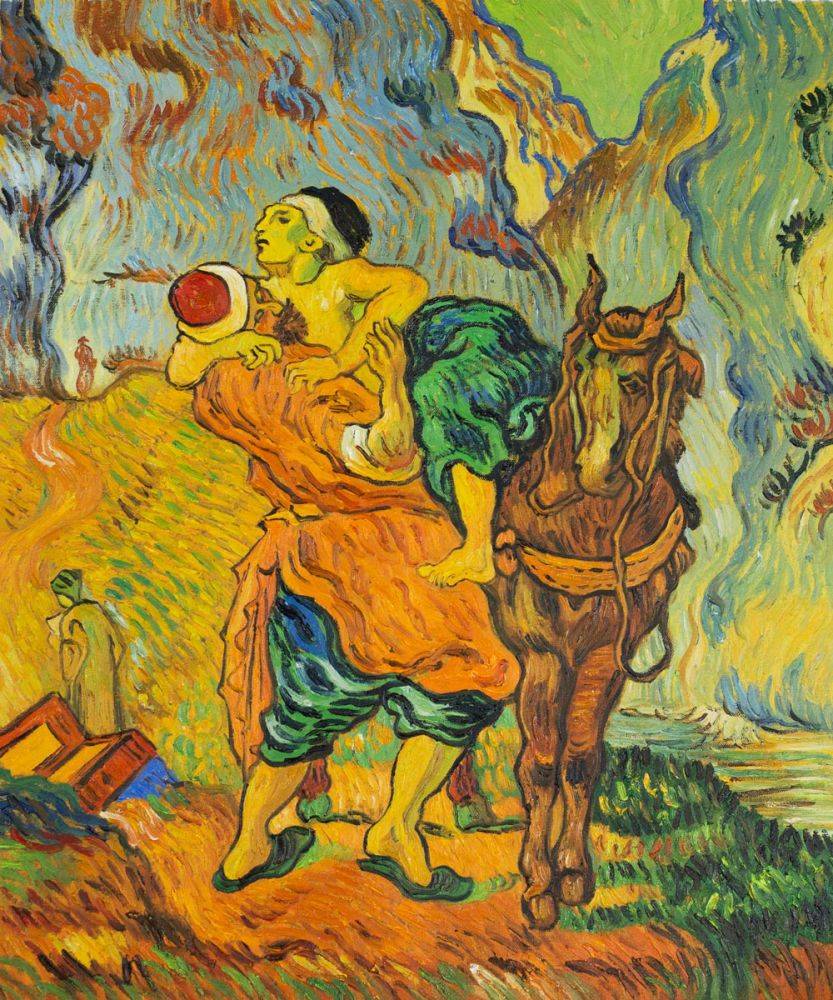

Good Samaritan Sunday“May the words of my mouth and the meditation of our hearts be acceptable to you, O Lord, my rock and my redeemer.” (Ps 19:14) Let’s jump right into this morning’s Gospel. I think it has to be the most famous of all parables – the parable of the Good Samaritan. And it begins with a question. The answer, which is the Good Samaritan parable, is so familiar that it can capture all the attention, and then the question gets ignored. But it’s the question that sets the stage for everything that follows. A lawyer, a man of precise definitions and expectations, is the questioner. A good contract lays out what is expected and what is paid. This congregation, for example, has a contract with me. It explains what the church expects and what I can expect in return from the church. The lawyer’s question of “‘What must I do …?’” asks Jesus what he is obligated to do in a virtual contract with God. In return for doing his part, the lawyer expects to be paid, which is the second part of his question: “‘What must I do … to inherit eternal life?’” The lawyer, as a lawyer would, approaches his faith as a contract of obligations and payments. This guy is not like Peter, Andrew, James and John who immediately left their fishing businesses behind to follow Jesus. He’s not like Matthew who left a lucrative tax collecting job to follow Jesus. He’s not impassioned. He only wants to know what must be done, just enough in other words to fulfill the contract, and then “‘inherit eternal life’” for himself. The lawyer has no qualms or questions about love God completely. What he needs Jesus to clarify is this notion of “love your neighbour.” Let’s try and think about this in terms of paying taxes quarterly. We approximate as closely as possible how much we’ll owe on April 15th. Then imagine though that our taxes need to be paid in full or face a heavy, harsh penalty, but that there will be no tax refund for anything we overpay. Imagine how upset we would be if we overpaid and wouldn’t get it back. That’s sort of like the logic of the lawyer. He wants Jesus to tell him what must be done so he can get into heaven, but he doesn’t want to go overboard with this love-your-neighbour-stuff. So he asks a second question: “‘And who is my neighbour?’” I have heard amazing sermons based on this parable that Jesus gives as His answer. I’ve heard it told from the perspective of the Good Samaritan, of the man who has been left for dead, and even from that of the priest and the Levite. But for me, at least for me right now, the key to unlocking this perfectly Christian parable is the context, that it is an answer to the question “‘What must I do to inherit eternal life?’” In answer, Jesus offers something completely, radically unexpected. Let’s give the priest and the Levite the benefit of the doubt that they are not completely uncaring men. Maybe we’ve been in situations ourselves where to help seemed dangerous. Maybe seeing someone hitchhiking on a dark road, for example. Do you stop or do you continue on wondering about the possibility of being robbed or worse? The priest and the Levite think through the options and choose not to do anything, but the Good Samaritan helps immediately, without thinking. He acts spontaneously, naturally. What the Good Samaritan did cannot be expressed in the language of “What must I do ..?” and the Good Samaritan does not act because of some reward about getting into heaven. The Good Samaritan acts because he can’t not act. When Jesus finishes the parable and tells the lawyer “Go and do likewise,” it’s a broad rejection of the whole idea of loving God and loving neighbour as a contract, if I do this then God gives me that. The parable speaks to Jesus’ expectation that there’s a better self within every person. The Samaritan would not have been accepted as a religious person by the Jews around Jesus or even as a good person, but here he is held up as the one who gets what God is all about, and what God hopes us to be all about. This had to be disconcerting. It’s really a whole new way of looking at humanity and human nature. It’s hope-filled. It's in no way contract.

Apollo 8 was the first time human beings left earth’s gravity and ventured out into space. It was the first time we left home in a sense. Some science historians consider this to be even more important than Apollo 11’s landing on the moon. It was our first step that would take us to the moon, the planets and then beyond. When the astronauts came around from the dark side of the moon, they captured the first-ever image of an Earth-rise. That’s this picture. Against the barren landscape of the moon and the darkness of the sky, one of them mentioned that the earth was the only colour out there in space. When we look at our home from this perspective, I hope we realize that we all live in the same house. We’re all in this together. In God’s eyes, we’re all one people, more similar than we’d like to admit. Maybe in the Good Samaritan parable Jesus is asking us to try and see like this, like from space, like from God’s perspective. Maybe our ideas of borders would become more all-encompassing. Maybe this perspective helps us humans become more humane, and maybe that’s what the parable of the Good Samaritan is trying to help us see, our shared humanity. Can we accept a new way to see? To see like God sees, that we are a glorious mess of colour all mixed together haphazardly, but oh so beautifully. Can we see that others and us aren't all that different, and can this Good Samaritan insight inspire us to compassion and empathy?

For this may we pray in Jesus’ name. Amen.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

NewsFaith, love and chitchat. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

Follow

|

|

SERVICE TIMES

Sunday 9:30-10:30am Children Sunday School 9:30-10:30am Nursery care available during worship DONATE Make a single or recurring contribution by clicking here |

FOLLOW

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed