“I think there’s one thing that can make it all better: editing.”Throughout the year, the Southern New England Conference of the United Church of Christ produces the Daily Lectionary for use by churches. These are the suggested readings for Monday, March 1st: Genesis 21:1-7; Psalm 105:1-11, 37-45; and Hebrews 1:8-12. I would encourage you to read these short selections as part of your Lenten practice.

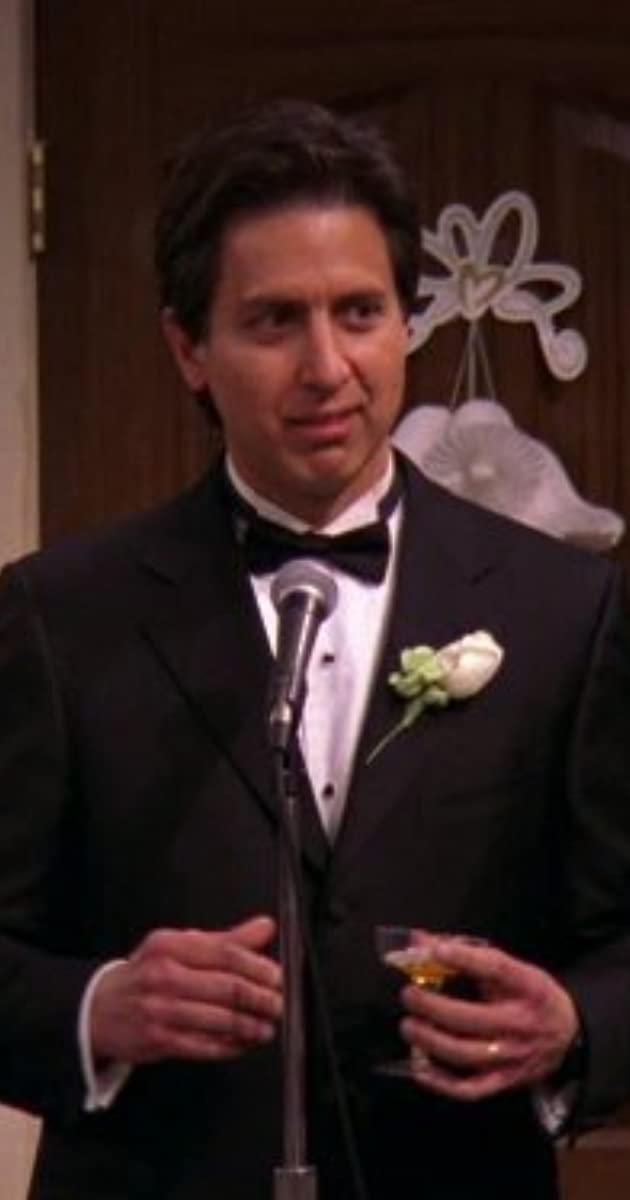

Biblical scholars have long noted that the books of the Pentateuch – Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy – give evidence of multiple authors. Few, other than biblical literalists, believe that these books were all written by Moses, as in the putative “Books of Moses.” This documentary theory is an impressive piece of work. The earliest writing is (J) and is named as such because of this author’s preference for the name of God, Yahweh, which was sometimes conveyed as Jehovah, thus (J). The second writing is (E) for God’s name, Elohim. The third is (P) and this stands for the priestly tradition. (D) does not enter our story today, but (D) is the source of Deuteronomy’s re-telling of the Law. J is a raucous story, uninhibited and primitive. Scholars see the hand of J in the passage: “So Sarah laughed to herself, saying, ‘After I have grown old, and my husband is old, shall I have pleasure?’ The Lord said to Abraham, ‘Why did Sarah laugh, and say, “Shall I indeed bear a child, now that I am old?” Is anything too wonderful for the Lord? At the set time I will return to you, in due season, and Sarah shall have a son.’ But Sarah denied, saying, ‘I did not laugh’; for she was afraid. He said, ‘Oh yes, you did laugh.’” (Genesis 18:12-15) J has little problem in showcasing the human, sometimes unflattering, side of these biblical stories. Sarah laughs at God’s preposterous promise of her being able to give birth long after “it had ceased to be with Sarah after the manner of women,” (Genesis 18:11) and God seems quite offended. P’s task is to round the rough edges of earlier stories such as this one and make them more seemly. In the Priestly tradition, Sarah, the mother of the People of God, can’t be left to laugh at God’s promise. Instead, from P, we receive today’s reading: “Now Sarah said, ‘God has brought laughter for me; everyone who hears will laugh with me.’” Now the laughter is not derisive; it is joyous. It is not the spontaneous, natural reaction of a 90-year-old woman; it is the pious acclamation on one blessed by God. This reminds me of an episode of Everybody Loves Raymond. It was Robert’s wedding day and all had not gone well, and somehow Raymond needed to make a toast to celebrate this awkward occasion. What he settled upon was this: “I think there’s one thing that can make it all better: editing.” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oVPcklJ8M0w ) The examples above are biblical editing within the biblical tradition itself. This is a sign of the Bible’s vitality. It’s not about undermining the inerrant Word of God. It’s about accepting that the words may change, but The Word remains. What came to be the biblical text shifted and changed as the people writing and reading these stories shifted and changed in their relationship with God. This editing reflected the sacredness of the relationship between the people of God and God. That relationship was living, changing and developing, and was far more significant than the unchanging words. That relationship was not bound up in the static words on the page, but in the lives, thoughts and faith of the people. This should be remembered when we read New Testament passages such as today’s from Hebrews, a passage that celebrates God’s immutability. Again, we need to be open-minded. Hebrews is addressed to Jewish-Christians who may be wavering in their newfound faith and might be contemplating returning to Judaism. To such an audience, the author of Hebrews emphasizes the continuity between the Jewish faith and the nascent Christian faith. Thus, he addresses God’s immutability. But Hebrews also speaks of the Son of God. This is traditional for 2021 Christians, but not for first century Jews. Son of God is a radical departure from the earlier faith. Change is present even in a passage celebrating the absence of change. Looking at it from the other direction, when Hebrews mentions “‘Sit at my right hand,’” this is a profound effort to elevate Jesus to the highest ranks of the holy. Jesus is above the heavenly angels. Jesus sits at God’s right hand. This remains an image used to this day in Christianity, but back in Hebrews it meant far less than it does today. In Hebrews, Jesus was glorified to God’s right hand, but Jesus still was not the fullness of God. Jesus was the Son of God, sat at the right hand of God, but God was something separate. In Trinitarian Christianity, this profound statement in its original form would be insufficient. It wouldn’t recognize Jesus as part of the Trinity, sharing in the very nature of the Godhead. Why? Because Christians had not yet progressed to the concept of the Trinity. Again, even in this passage on immutability, change permeates the text. Lent is a journey. Faith is a journey. We see it right in the textbook of our faith. To grasp the holy doesn’t mean to grab onto the past as if that’s when God was more interactive with us. To grasp the holy means to meet God, to meet Christ, where we are now. This is the promise offered through our Lenten regimens, to bring Jesus closer to us, and us closer to Him, our crucified God. If you’d like, here is the link to the Massachusetts Conference’s daily reading schedule: www.macucc.org/lectionary.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

NewsFaith, love and chitchat. Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

Follow

|

|

SERVICE TIMES

Sunday 9:30-10:30am Children Sunday School 9:30-10:30am Nursery care available during worship DONATE Make a single or recurring contribution by clicking here |

FOLLOW

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed